Why, just the other day I was taking my mom for a drive, on a Saskatchewan prairie road, in a rented Jeep Grande Cherokee. We had flown in that morning on a mission to say goodbye to the land, the family farm, the mythical homestead, the site of her birth.

To get there, drive a ruler straight highway until the Borden turnoff, then through a town that time forgot, onto a rolling gravel road and finally, to a rutty dirt turnoff that descends down down. Down, past a huge slough and eventually, to the edge of 160 acres.

Of course, the upgraded Jeep Grande Cherokee (only ten dollars more a day! Plus insurance) balked at the single lane mud track. So, we backtrack to the home of Bob, the affable farmer who leased the land from my Uncle for decades.

I have met Bob several times in my life and remembered him as much older than I was, closer to my Mom’s age. Turns out, I have been mistaken. Bob is one of those rare and wise spirits who are (as George Bailey’s father says in It’s A Wonderful Life) “ just born old”. And by that I mean ageless and grounded. Also gracious.

We arrive around noon, a sunny day during harvest. No one just drops in for a visit during harvest. My mother though, is relentless. I reluctantly get out of the Jeep where Barnyard Dog, a protective and gorgeous Husky)\, growls an uncertain hello.

Alerted, a young woman opens the front door of the house and moves toward us, two kids in tow. I explain who I am, (city person) why we are here (to visit the farm her family has just purchased). She calls her father in law on the radio.

We talk about the weather: It has rained heavily the night before, so despite the sun, there’s no harvesting until it is drier. Incredibly, they are NOT busy. My Mom nods, as if she knows this (does she? She DID grow up here), and a requisite and durable Ford pulls up into the drive.

Bob ambles over, ball cap, overalls, shy smile. He is definitely not 86.

I introduce myself. Despite our recent phone chats, we had not actually seen each other since my Grandmother’s funeral almost 20 years ago. He moves toward my Mom, who, like the queen, waves from the passenger window.

They chat like old friends, and she congratulates him on being the winning bidder for The Land. ‘”Oh!’ he says, embarrassed, “do you want it back?

She does not want it back, and neither do I. After months of debating the wisdom of owning hard-scrabble prairie, it became very clear it belonged with someone who visited more than once a year. Someone who knew how to coax crops, and when to harvest. Someone reliable. Not a corporate farm (those are increasingly more common in this once insulated province), and certainly not the BC based retiree investor buying land with Credit Union money. Word around here is he shrewdly rents it out to cash strapped farmers who already work it, then heads back to the coast until the next auction.

Outsiders are still suspect.

“I’m glad it’s gone to you”, my Mom says earnestly.

We all are. Who better than the son of a farmer, whose family continues to make a living 13 km from the nearest paved road, in the centre of the Saskatchewan Universe? He knows everything around here, every old house and weathered barn, every dirt track and deep slough. This is his kingdom and he offers my mother, the cane toting dowager (and her city born daughter), a tour.

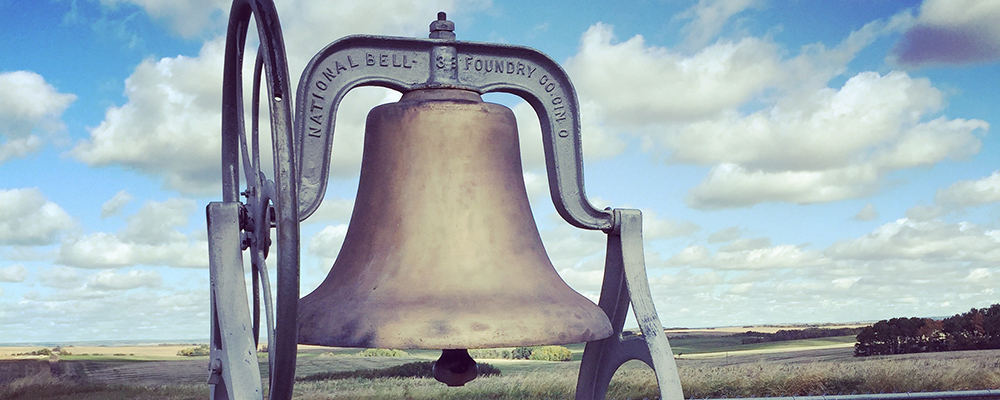

He helps my Mom into the passenger side of his truck. I clamber into the back, and we bounce along, stopping at the old church. The bell is still there, the strangely modern wrought iron Orthodox crosses, the small white building. I take photos. Although we go inside the church (Bob says it’s too expensive for a priest to visit here anymore), we do not go to the graveyard to see where my mother’s brother lies. There are several eerily tiny graves, testimony to a time before readily available penicillin.

Past the church up a hill, then down through tracks bordering The Big Slough, up and over and we’ve arrived. The house burned down years ago, but the barn still stands, better than I remembered it, prouder, upright. The graineries, strengthened by chains on the inside, to support the weight of shifting grain, seemed indestructible, over 100 years old and solid. A shed, door open, was littered with the detritus of generations: a fishing pole, peanut butter tin filled with rusty nails, a crib stored in the rafters. Bob and I take turns pointing out discarded treasures, a Depression era game of Eye Spy.

“Was this the house?” I ask, wading through weeds as high as my hips. “Come on in…” he gestures, as if opening an imaginary gate. Then, more urgently, “Wait! Watch the hole there.” I stand on the edge of what used to be the root cellar, the creepiest place my sister and I could imagine. Shelves of preserves, sacks of potatoes, and the smell of earth and rot. We imagined the bravery of our teenage Mother, pulling up the trapdoor and descending the damp ladder to fetch food from the cellar. Or the entire family, huddled there during a tornado warning.

“There’s a well out there too.” My Mom cautions from the truck. Another hole, another story. The well is where my Aunt Minn almost drowned. I step carefully, point my camera and shoot, the silver barn against the cornflower blue sky.

Bob leads the way to the barn, the smell of ancient livestock heavy like country aftershave.

It’s dusty, full of cobwebs and abandoned swallow’s nests. “Look at the manger”, he says, indicating the trough. “Manger” is a funny word, I think. More biblical than practical. But there it is. “It’s worn so soft, almost like it has been carved”, he marvels. And he’s right. You can see where heavy heads have grazed, rubbing and smoothing the rough board for lifetimes, carving what now looks like a strange folk art headboard.

He changes my Point of View, seeing beauty where initially I saw dust and desolation.

Bob is the right person to own this land. He knows what it will yield, what to keep and what to lay to waste. He notices the weather, slipping seasons, later harvests. He points out a beaver dam on The Big Slough, wild horseradish, moose tracks.

On our way back to his farm, to the rented Jeep and the chatty daughter, two dragonflies fly into the truck. “Ohh,” my mom whispers, “they are so beautiful, so colourful.”

I have a strange thought: Could it be my grandparents returned as dragonflies? In the same way my friend recognizes her Dad in the bunnies that occasionally stop to get her attention, or my cousin’s conviction her mother returns to her as birds? My grandmother would make an excellent dragonfly: Majestic, misquito eating, practical, purposeful, the bearer of strange beauty.

My own mother will probably return as a butterfly, still magical, capable of long migration. She ached to escape this place and now has orchestrated her return, a brief journey, landing lightly, then moving on.

Bob helps my Mom from the solid truck to the city-shiny Jeep. He is so kind to her, respectful, a solid arm for her to lean on. I stand awkwardly as we say goodbye, glad sunglasses disguise my cry baby eyes. Tears triggered by gratitude for this farmer I barely know, the steward of the land, of my Mother’s stories. I give him a sudden, awkward hug, surprising both of us. He, like so many things on this journey, is a miracle. An Angel, my Mom calls him later, on our drive back to Saskatoon.

A gift of this Autumn drive, a keeper of history, a lover of the land.